Ryan Pickering, Renewable Convert, Indigenous Advocate, Researcher - February '23

Ryan Pickering converted to nuclear energy after a 13 year career in the solar industry. (Photo courtesy of Pickering)

Ryan pickering, once a devout solar career man, fell into disillusionment and into love with nuclear. the love story we needed to hear.

Growing up in Los Gatos, California, most environmentalists around Ryan Pickering rejected nuclear energy as a viable energy source, he said. Always interested in the environment, as a child Pickering created science fair projects on energy and successfully lobbied politicians in Livermore to repair broken wind turbines.

In 2009, after he graduated college, he embarked on a 13-year career in the solar industry, an admirable career path that he believed was the right thing to do for the environment. Later, he said that everyone around him supported renewables without question and it seemed the “cool” thing to do.

“It was an opportunity to make an impact. And there was this implicit goodness and merit to all renewable energy, just as a concept,” Pickering said. “I felt like I had this moral platform to really go crazy on, and worked 60 plus hours a week.”

Anti-nuclear sentiment was common in university classrooms, Pickering said. Mark Z Jacobson at Stanford suggested in lectures that supporting nuclear energy undermined the climate.

“He said every second you think about nuclear energy is a distraction from an actual solution that is wind, solar storage, and wind, water, solar and storage,” Pickering said. “He made you feel guilty for even considering it. And it's been incredibly effective.”

With time, Pickering found moral problems with solar that would eventually lead him to embrace nuclear power. Uighur slave labor in the construction of solar panels was among the most pressing issues for Pickering. When he complained to coworkers, though, he said they responded with indifference and told him to focus on the money.

Identifying as an ideological leftist, Pickering was also bothered by the large push for net metering, a policy he described as essentially a regressive tax on the poor. Affluent coastal elites who could afford to install solar panels received massive discounts on their electricity bills while renters and homeowners who could not faced higher electricity bills, and essentially subsidized the cheaper electricity of the wealthy.

“That just really poked a hole in my narrative about the egalitarian nature of solar,” Pickering said. “People started ignoring moral claims because there's an incentive.”

When he read an article announcing the premature closing of Diablo Canyon in 2021, partially based on a supposed rapid deployment of renewables, Pickering said he became a nuclear activist. As someone involved with renewables, he knew their limitations, and that closing Diablo would be a large blow to the climate.

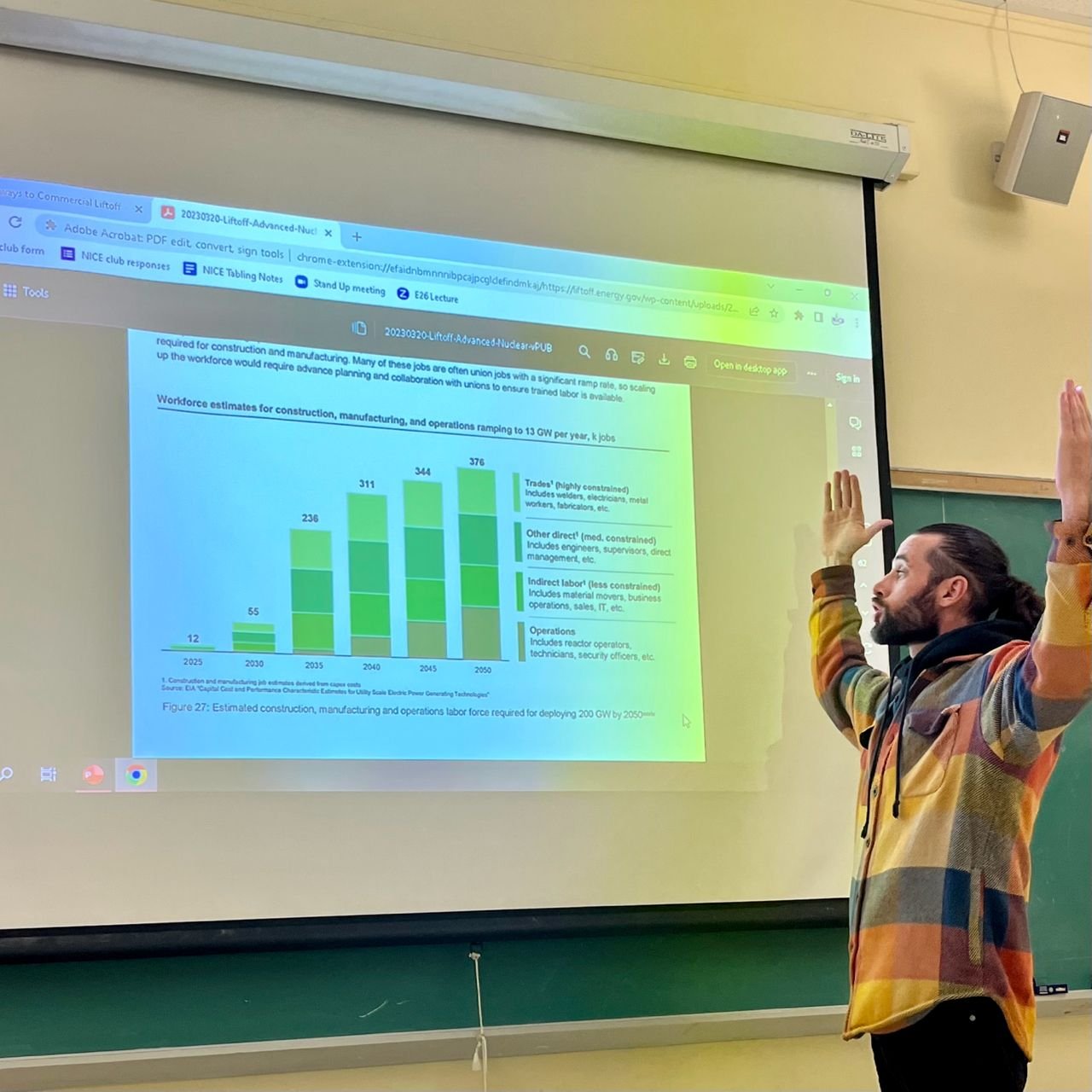

Ryan Pickering delivering a lecture for the pro-nuclear research group at U.C. Berkeley, Nuclear is Clean Energy (NiCE). (Photo courtesy of Pickering).

Pickering said he believes in an abundant energy future that includes renewables, but that they must be paired to a nuclear-centric grid to transcend fossil fuels. For the well being of the working class and of the environment, he said the notion of 100% renewables must be rejected.

As an independent researcher at U.C. Berkeley, Pickering formed a student group open to the public, Nuclear is Clean Energy (NiCE), where individuals can present their research. It also acts as an open forum for nuclear engineers and nuclear advocacy. The group occasionally phone banks in attempts to save nuclear plants as well.

Pickering also participated in campaigns to legalize nuclear energy in Berkeley (a Nuclear Free Zone since 1986), California, and everywhere. According to Pickering, these efforts are some of the most important outpourings of the Save Diablo movement.

Advocating on behalf of the YTT Northern Chumash Tribe stands out as among Pickering’s proudest work he said. The tribe of less than 100 has been attempting to regain their ancestral lands for generations, including the site of Diablo Canyon.

A land back process could name the tribe, who are not federally recognized, as tribal stewards of the plant, with around 9,000 acres of land, according to Pickering. He believes this process is important in the context of the history of nuclear energy, including poorly regulated uranium mining that led to the deaths of many Dine people. Many abandoned mines remain and have not been cleaned up.

The tribe, unlike many in the nation, have spoken favorably about nuclear power and possess an impressive knowledge of the energy source, Pickering said.

“The state of California needs to do the right thing here and recognize real people that have lived here for 10,000 years,” Pickering said.

As an activist, one of Pickering’’s most important activities, he said, entails “signal boosting”, or supporting the pro-nuclear movement online. Several years ago, as the movement started to grow, he said a lack of support on social media like Twitter could feel alienating, something he tried to remedy.

“I wanted to provide solidarity to this movement and try to grow it, make it palatable,” Pickering said. I've put a tremendous amount of effort into aggregating us together and shoring up the movement.”